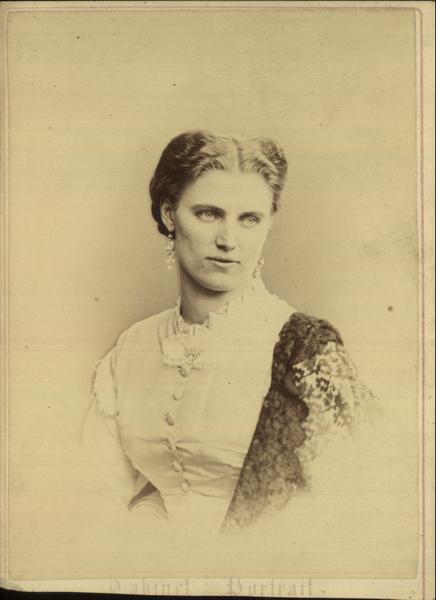

When you're a historical author, you do a lot of research. Pair all of the book-specific research with a degree in Victorian British History with a focus on gender and sexuality, and I've got more random facts kicking around in my head than I know what to do with. Today we're taking a closer look at a game changing fashion trend in Victorian Britain.

Of all of the fashions that jump to mind when one says "Victorian England", the crinoline is probably the most distinctive. The massive, bell-shaped skirts of the late 1850s are iconic in both their size and impracticality (sitting in one of those must require great skill and a well-timed prayer that the hoops didn't go flying over your head). They are romantic because nothing we wear now bears much resemblance to the floor-length skirts that ladies adopted during this era.

Skirt Size and the Development of the Artificial Crinoline

Undergarments are what makes much of women's fashion in the 1800s possible. The crinoline is no exception.

In the first half of the 1850s, women relied upon layers upon layers of petticoats to hold out their skirts. Check out 0:26 of this clip from Gone with the Wind. Scarlet pulls on a petticoat made of layers and layers of flounces.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=92kLpKuRJfo

Often horsehair warp or wool weft was use, but the problem was that these material are both heavy and hot. Women were quite literally weighed down by their undergarments not to mention the yards of fabric required to make up their actual dresses.

The artificial crinoline was a game changer. It's essentially a large cage of wire hoops held together by vertical tapes, and it did away with the need to layer petticoats on in order to fill out a dress. That in turn kept the layers of fabric forming a woman's skirts out of her way, allowing her greater mobility (Cunnington, 188).

There are conflicting stories about who introduced the artificial crinoline into society. Elizabeth Ewing credits the Princess Eugenie, the wife of Napolean III, with both wearing one and bringing a grey one covered in black lace and pink bows as a present for Queen Victoria on a visit to Windsor (Ewing, 47). C. Willet Cunnington disagrees, claiming that it was in use before Princess Eugenie got her hands on the style and that she is simply the most prominent early adopter.

Whoever is responsible for the crinoline, that woman changed the silhouette and undergarments of Western women for decades.

A word about typical trends in crinoline-reliant dresses. From 1857-1859, fashion favored dome-shaped skirts. Dressmakers did away with the flounces, tucks, and fussy details of an earlier era (they did not suit the new line of the skirt that thrust out into space on its own). Instead, double and treble-layered skirts with vertical trimmings were commonly seen. Short corsets with a highly defined waist and little hip definitions were also common in this era.

Crinolines, Class, and Gender

First advertised in England in 1856, the crinoline exploded in popularity in a few short years. Looking at the dresses made to accommodate this kind of undergarment, you might think that this would be a fashion exclusively worn by wealthy women. Dresses could reach four or five yards in circumference and required 18 yards of expensive fabric to construct a dress. But as Cunnington writes, "It served as a barrier against the aggression of the Lower Orders, who were kept at arms' length--until even the Lower Orders themselves adopted the fashion" (170).

Women went crazy for crinolines. An often-cited fact to show the popularity of the crinoline is that in 1863, Staffordshire potteries lost 200 pounds worth of product due to the wide skirts of working women accidentally sweeping shelves clear (Willet & Cunnington, 154). That is a lot of smashed pottery, but it didn't persuade workers to leave off their crinolines.

Aside from the fact that crinolines kept women's skirts clear from their legs and relieved them from the burden of petticoats to hold out their dresses, historians argue that the fashion gains popularity during an era when women were demanding greater recognition in public life. Much of the rhetoric around women's roles at this time talks about the separation of the public (male) and private (female) spheres. A woman was expected to be the Angel in the House and leave things like commerce and politics to her husband. Yet in the 1830s, the men and women behind the early suffrage movement forced British politicians to debate the idea of a woman's right to vote during the Great Reform Act of 1832. Women wouldn't win the right to vote for decades, but they continued to make small but significant strides in the meantime. The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 granted women the right to divorce and abolished adultery as a criminal act.*

Some historians of fashion argue that as women asserted themselves in the public sphere, they also asserted themselves through their choice of these massive, crinoline-enabled dresses. The skirts literally take up more space, demanding that people watch out and make way for their wearer. It's impossible to ignore a woman walking down the street or gliding into a ballroom when she has a five-yard circumference. She demands attention.

The Fall of the Crinoline

"The notion that ease and comfort must be sacrificed in order to express social rank, had previously governed the design of fashionable clothing. Now, at last, it seemed too great a price to pay." (Willet and Cunnington, 152)

As with every fashion, the crinoline had its heyday and then was set aside for another trend. First, the crinoline was reshaped. In the 1860s and 1870s, it starts to push towards the back, putting more emphasis on the fanned back as opposed to the large, domed sides. Then, skirts eventually slim down. The crinoline was simply too big to be practical.**

If you are interested in more articles like this or would like to stay up to date on release dates and other news, please subscribe to my newsletter!

More Victorian fashion is available on my Tumblr ReallyOldFrocks.

*Up until 1857, obtaining a divorce was a difficult, expensive, embarrassing task. It required an Act of Parliament, and few people had the means to pursue a case. Unsurprisingly, it was also doubly difficult for women to successfully petition for divorce. A woman had to prove two complaints against her husband such as adultery, abuse, and neglect. A man? He just had to prove one of those complaints during the proceedings. Making such a case would be embarrassing, but he had the chance to bounce back socially. A divorce case would almost guarantee a woman's ruin whether she was the party at fault or not.

**The physical dangers of the crinoline range from the very real to the ridiculous. There are anecdotes about skirts catching fire and women falling over only to wind up with their skirts over their heads (one story even includes the Duchess of Manchester). Even with quilted petticoats draped over the cages, in the winter the skirts were drafty with nothing hanging around legs legs to keep them warm. There was also a problem of propriety. If you sat down the wrong way in a crinoline, the entire drawing room got a very clear look at your undergarments. This was not an era where anyone got to look at a lady's undergarments. How scandalous!

Sources

Cunnington, C. Willett, English Women's Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations, Dover Publications, 1937

Cunnington, C. Willett & Phillis Cunnington, The History of Underclothes, Dover Publications, 1951

Ewing, Elizabeth, Fashion in Underwear: From Babylon to Bikini Briefs, Dover Publications, 1971

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.

This Sunday was Marathon Day here in NYC. I, like many New Yorkers, live right near the route. While I love the marathon, sometimes the crowds can get a little rough. This year I cheered on some of the runners earlier in the day and then left the neighborhood to do something I never do. Dear Reader, I went to the Met on a Sunday and took a boatload of photographs.